Sam’s Blog: Episode 1

My Lawn Is a Lovely Shade Of Brown

by Sam Schuchat, Coastal Conservancy Executive Officer

A great many lawns are a lovely shade of brown in California right now as we are well into the third year of the worst drought since the 1970s. That includes the lawn around our state capital, which the Department of General Services let die. There isn’t very much anyone can do in the short run about the drought, other than conserve as much water as possible and hope that next winter is at least a “normal” winter if not a wetter than normal winter. In the long run however, there are plenty of things we can do, particularly in our coastal cities, to adjust to the realities of periodic droughts and the impacts of climate change on our water system.

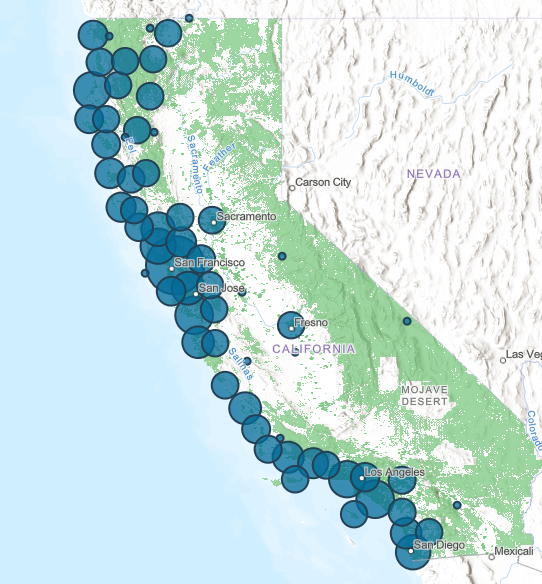

If you live in one of California’s big cities along our coast, much of your water comes from far away, either the Sierra Nevada snowpack or the Colorado River. These sources have suffered the most in the drought, and are most at risk over the long-term in as the southwestern United States warms up. At the same time, a great many of our urban areas have local water supplies that are not well served by the ways in which we have engineered our cities over the last century.

Basically, our cities have been designed to capture whatever rain falls on them and move it into the ocean or San Francisco Bay as quickly as possible. This made a lot of sense for cities that were flood prone in an era when we felt assured of safe water supply. This doesn’t make much sense when we are short on water.

In addition, the way we have plumbed our cities creates another problem. All of that rainwater runoff, as well as runoff during the dry season from washing cars, watering lawns, and so on, moves all of the nasty stuff that accumulates on our sidewalks and roads into our ocean and bays as quickly as possible. The technical term for this is nonpoint source pollution, and it is the next great frontier of water quality in California. Many of our cities, and eventually all of them, are now under orders from the Regional Water Quality Control Boards, to drastically reduce the amount of pollution flowing from streets and sidewalks into the ocean and other local water bodies. The expensive way to deal with this problem would be to treat the runoff, but nobody can really afford that.

The State Coastal Conservancy has been interested in less expensive ways to treat this problem for quite a long time. The solution, in theory, is simple. If our urban landscapes were more permeable to water, then rain when it falls would seep into the groundwater, be cleaned by the biological action of organisms in the soil, and be available for human consumption. Recently, the Coastal Conservancy has:

-

Funded the Los Angeles Department of Public Works to test a variety of water capture techniques on Riverdale Ave., a street which leads to the Los Angeles River. This led the city to adopt these techniques and principles into their street manual, the document that tells city engineers what to do when it is time to repave the street.

- Along with the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, funded Community Conservation Solutions in Los Angeles to take a look at publicly owned land in the county that could be made over into parks or other kinds of permeable surfaces that capture rainwater, replenish groundwater, and increase local water supply. We are now collectively taking a look at the potential to decrease the amount of water that has to be pumped into Los Angeles from a great distance away by doing this.

- Funded Water LA to bring together local experts, residents, and City agencies in an “urban acupuncture” approach to water sustainability in the Los Angeles River watershed, essentially helping homeowners retrofit their homes and gardens to capture rainwater, plant native species, and so on. Because neighbors helping neighbors is a program requirement, this also helps build community with each project.

Obviously any and all of these efforts will have to be drastically scaled up to make a dent in our water supply and water quality problems. There are severe obstacles to doing so, including funding, bureaucratic inertia, and the many different entities, even within a single city, that must be persuaded to adopt these techniques as standard practice. Even the longest of journeys starts with a single step though, and our hope is that these and other pilot projects will help get the ball rolling on a new way of handling water in our urban environments.

Latest News

- Press Release: Coastal Conservancy Awards over $40 million for coastal access, restoration, and climate resilienceOakland, CA (4/18/2024) – Today, the Board of the State Coastal Conservancy approved grants totaling over $40 million for coastal access, restoration, and climate resilience. Among the grants awarded today are: A grant of up to $6,000,000 to Humboldt County Resource Conservation District to undertake the North Coast Wildfire Resilience Planning and Implementation Grant Program, which […] (Read more on Press Release: Coastal...)

- Sea Otter Recovery Grants RFP Now Open!The California State Coastal Conservancy announces the availability of grants to public agencies, tribes and nonprofit organizations for projects that facilitate the recovery of the southern sea otter along California’s coasts. The California Sea Otter Fund is one of the state’s tax check-off funds that allows taxpayers to voluntarily contribute to the recovery of California’s […] (Read more on Sea Otter Recovery...)

- Coastal Conservancy Public Meeting in Oakland – April 18Meeting Notice Douglas Bosco (Public Member), Chair Marce Gutiérrez-Graudiņš (Public Member), Vice Chair Joy Sterling (Public Member) Jeremiah Hallisey (Public Member) Wade Crowfoot, Secretary for Natural Resources; Bryan Cash and Jenn Eckerle (Designated) Caryl Hart, Coastal Commission Chair; Madeline Cavalieri (Designated) Joe Stephenshaw, Director, Department of Finance; Michele Perrault (Designated) Senate Representatives Benjamin Allen (District […] (Read more on Coastal Conservancy Public...)

Help Save Sea Otters at Tax Time

Help Save Sea Otters at Tax Time